More and more, we see IT organizations gravitate towards and adopt event-driven architectures (EDA). Some of them know exactly what they are getting into; others not so much. On a personal level, I love EDA. My entire career is built on the base of EDA. When event-driven architectures are done well, I find that life can be rather simple. In a perfect world, adding a new piece or feature to our event-driven puzzle becomes effortless. However, I recognize that event-driven architectures can be difficult to adopt; they have a steep learning curve that requires time to get right as well as the correct infrastructure and expertise. I’ve seen event-driven architectures gone WRONG, but that doesn’t mean event-driven architectures are bad, it just means that it may not have been right for you… Yet.

So, when is an organization ready for event-driven architectures?

To oversimplify, event-driven architecture is a software design pattern that allows for information/data or “events” from one system to be communicated to other (potentially unknown) systems. Commonly done through the use of an event broker, a.k.a. message-oriented middleware, where data is stored into message queues/topics and produced/consumed by clients (publishers/subscribers). Now that that’s out of the way, let’s see if EDA is right for you!

If you’ve never dealt with event-driven systems, then the decision to turn your organization’s underlying architecture from a traditional model to an event-driven model is a difficult one. After all, our traditional model has provided us with so much success! It is the backbone of our business, so why would we want to change it?

Inevitably, there comes a time when your organization’s growth reaches a breaking point. That breaking point only surfaces when you introduce enough actors to your domain. An actor can be thought of as a group of users or stakeholders that require the system to change in some way. These actors all have their own wants and needs, but it’s not so easy keeping things cordial amongst actors. Occasionally, the desires of one actor directly interfere with the desires of another. This creates a tension within the organization and makes decision-making that much harder, thus stunting your growth. How could we possibly keep all the actors happy?

“A module should be responsible to one, and only one, actor” — Robert C. Martin

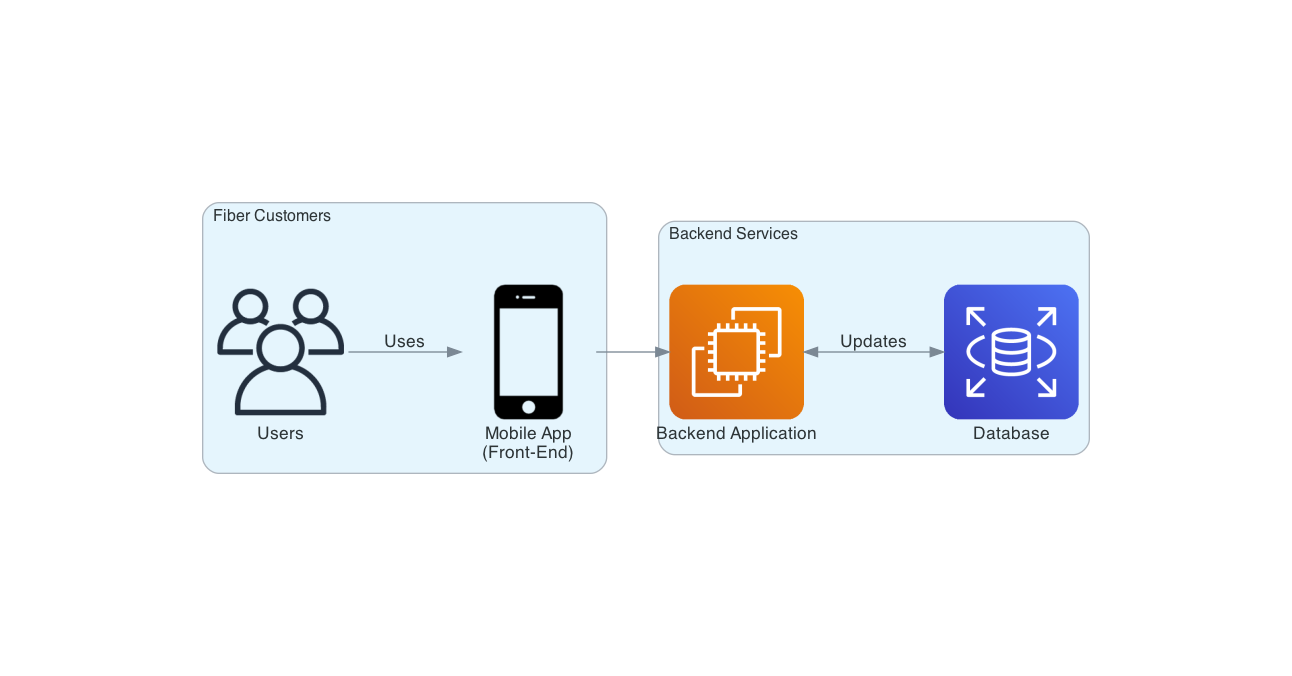

Consider the following simple application architecture, where we have fiber customers interacting with a mobile application to help manage their fiber accounts and services. When a customer performs an action in the app, it will communicate directly with our backend service, perform some super fun and complex business operations as well as propagate some changes to our database.

Nothing too crazy here. This is something we all may have experienced before in some capacity (professional or otherwise). The best thing about this architecture is that in many cases, it just works! Our customers are happy that the app is bringing them value via the ability to easily manage their account through the app instead of having to call in and speak with a representative. Additionally, our business is happy that our customer base is growing as a result of our easy-to-use application, giving us an edge on the competition. Thus, we’re all on cloud 9. Overall a great success. But what happens next after success?

Where there is success, there is growth! Just because something is successful doesn’t mean it’s finished. Software is rarely considered finished.

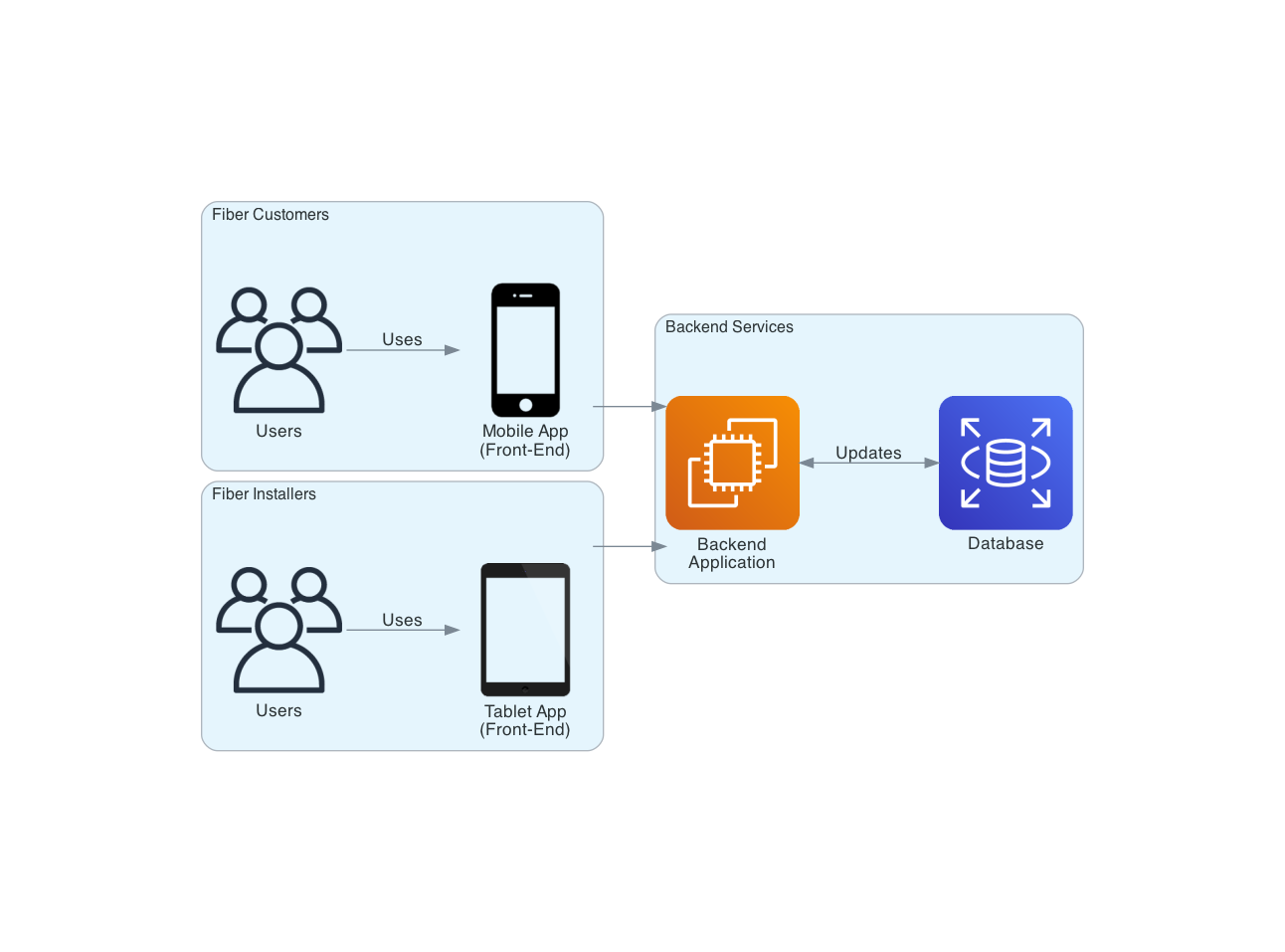

Consider the following, with the success of our application, our business now sees an opportunity to introduce another actor into the space (another revenue stream). This time, instead of only serving fiber customers, we will now introduce fiber installers to our workflow. Our fiber installers have their own front-end application (a tablet) that has access to the same tools and services offered to our fiber customers. With the added bonus that fiber installers can provide a discounted rate to our customers when onsite.

Here’s where conflict starts. It may not be so simple to just change the rate for our services depending on the actor. Installers need access to their own billing methods and options. These billing methods should not interfere with those that already exist for fiber customers, or the business could potentially lose a fair chunk of change by charging incorrect amounts to our customers. Suddenly, to make this seemingly simple change requires an expensive and time-consuming regression test!

The result? Changes are slower, more expensive, and become progressively more taxing on our common infrastructure. However, we do have a solution!

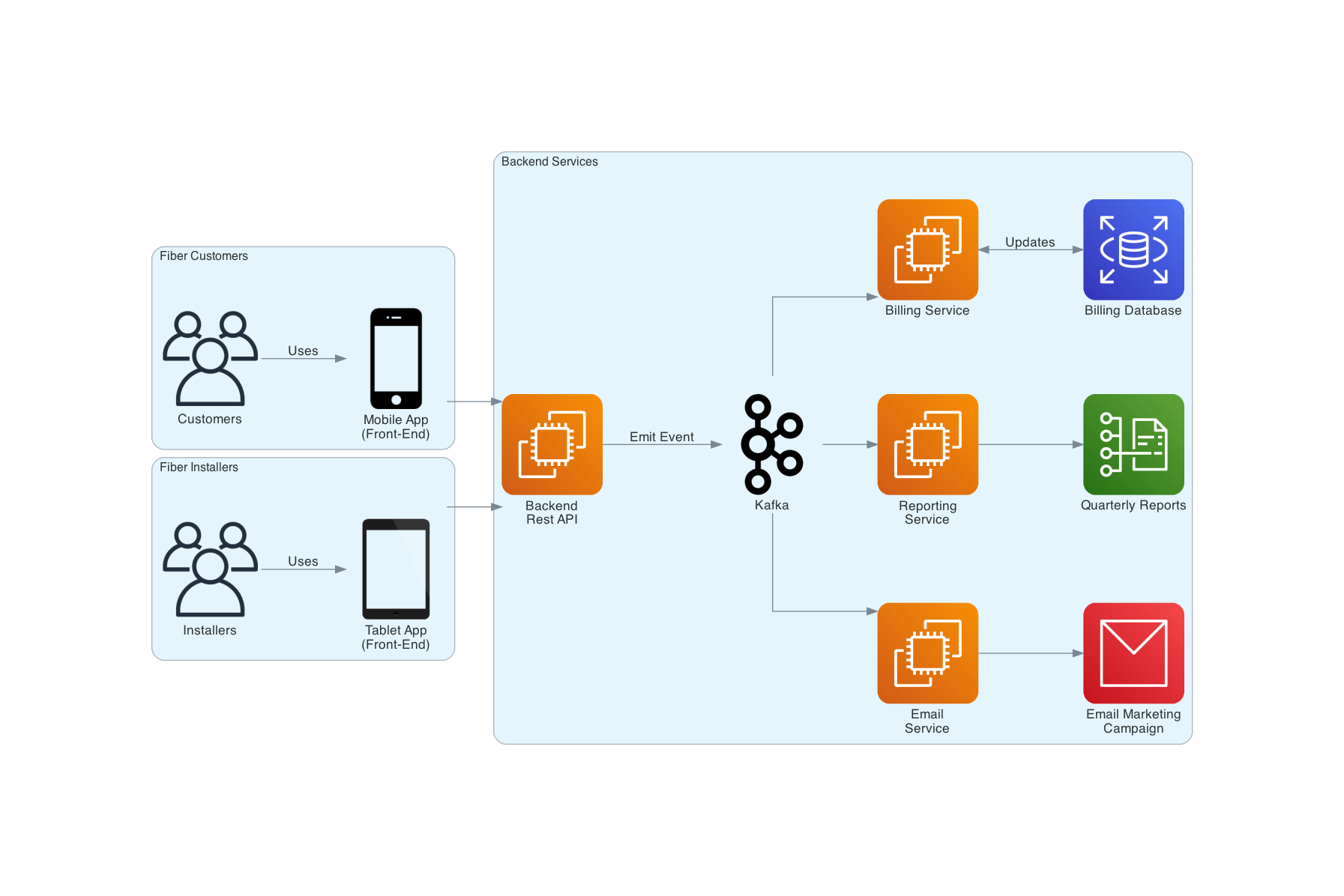

In comes our event-broker (Kafka). For those unfamiliar, Kafka is a distributed event streaming platform, meaning that it’s an expert at distributing messages from system to system in near real-time. With Kafka, we introduce an event-driven backbone for service-based architecture. This backbone is the piece that finally allows us to decouple our actors from each other by promoting the production, detection, consumption of, and reaction to events (Event-Driven Architecture). We do so by first modifying our original application architecture. The backend REST API that our actors used to communicate with no longer handles the complex business logic and operations it did in the past. Instead, that service will now emit events onto our backbone. These events provide a bunch of information, such as what action was performed and by whom. Multiple services can choose to listen to specific Events emitted onto Kafka, and those services can choose to perform actions on those events. By changing our architecture from a request-reply model to an event-driven model, our actors are now fully decoupled from one another.

For example, we now have the capability of separating our billing service for customers and installers. The billing service for customers will ignore any events that come from installers and vice versa. No regression tests are necessary as these services are no longer tightly coupled, and better yet, you open your architecture to extensibility. Adding a new feature becomes a mere extension of the infrastructure we have in place. Want a separate email marketing campaign service targeting customers when they browse a new fiber plan? Go right ahead and add a listener to Kafka.

In short, it’s all about the actors. Actors determine whether you should even consider adopting event-driven architectures. If you have a large (or rapidly growing) number of actors, then the efforts you put into establishing an event-driven backbone for your organization can be planted, and the fruits of your labor will bloom with each actor introduced to your system.

Now the question becomes, how do we build our Event-Driven Systems at scale?

Originally published on Stories from the Herd